Home to impossibly steep, terraced vineyards and some of the best riesling in the world, the Mosel is the oldest and most renowned of Germany’s 13 official wine regions. While I love rieslings year-round, I am particularly drawn to them in the spring and early summer when the farmers market is bursting with seasonal produce. Asparagus risotto, soft-shell crabs, and the green garlic compound butter (!!!) that I have been putting on everything I eat these past few weeks. Delicate and refreshing riesling is the perfect match.

Geography & climate

Located near the border of Belgium and Luxembourg, the Mosel is just about as far north as you can reliably grow grapes. Your options for what can successfully grow here are quite limited. Dominated by riesling, which makes up about 60% of all grape production, the region also grows müller-thurgau, elbling, and pinot blanc, plus small amounts of red wine (~10% of production).

German wine regions are almost all located along rivers, which act as a moderating influence, adding humidity, reflecting heat and sunlight, and helping to create microclimates sheltered from the mountains. Areas that face south receive up to 10 times more sunlight during parts of the year than those facing north. And vineyards located on slopes receive even more concentrated sunlight than flat land. The best vineyards are located on steep slopes (at or over a 30% pitch) with the south-facing plots demanding the highest prices. These specific constraints mean that location matters.

The soil in this region is primarily slate, which has a few benefits for growing wine here. The vineyards are able to quickly drain water during the wet growing season. Plus, slate’s heat retention properties protect the vines during cold seasons.

While the steep slopes are the most reliable way to ripen grapes, they are also the most labor-intensive and dangerous in the winemaking world. Steep slopes mean that machine harvesting can be tricky (or impossible). Add in the constant risk of soil erosion, constant care and upkeep, and the business of producing wine becomes a tricky one.

Sub-regions

The Mosel is informally divided into thirds, the Upper, Middle and Lower Mosel. If you’re looking at a map, remember, the Mosel actually flows north to the Rhine. So, the Lower Mosel is actually the most northern area and the Upper Mosel is to the south. Obviously, the Mittlemosel lies between these two regions, where the Mosel is at its twistiest and carves its most picturesque landscape — and also where its wines are the most magical.

History

The Romans originally started growing grapes along the Mosel and Rhine rivers to supply wine for their soldiers. Transporting wine from Italy was too expensive and difficult but you can’t run a global empire without a reliable supply of wine!

The region benefitted from the expansion of Christianity during the Middle Ages, with Benedictine monks traveling from Burgundy to the Mosel, bringing their advanced techniques and deep knowledge of viticulture with them. In Burgundy, the monks developed the basis of terroir-driven winemaking, focusing on site specificity and its ability to produce distinctly different wines from the same grape variety.

Their practice of careful observation and documentation was invaluable in regions like Mosel, where the steep slopes and varying microclimates required a nuanced understanding of viticulture. All of this greatly improved the quantity, consistency, and quality of wine produced in Germany.

One of the wineries established by the Benedictine monks, Staffelter Hof, is considered the oldest operating winery (and actually one of the oldest registered companies still in operation!) in the world, dating back to 862 AD. The monks were given land on the banks of the Mosel River by a Roman emperor to set up vineyards, which they used to produce wine for nearly twelve centuries. This winery has managed to stay incredibly relevant, achieving a cult-like following in the natural wine world. It’s arguably the most forward thinking and experimental winery in the Mosel Valley today.

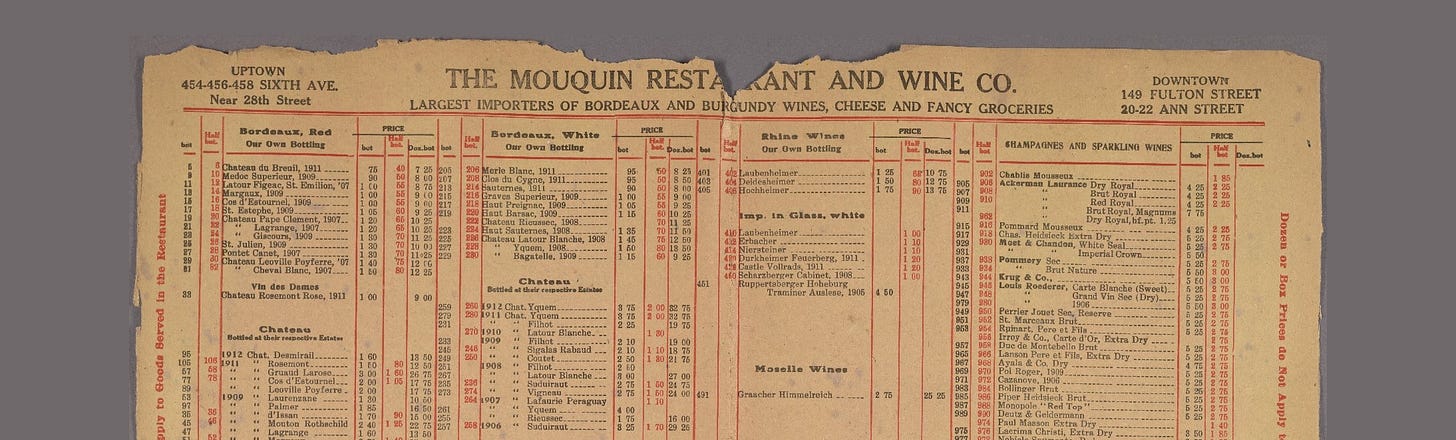

By the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, German riesling had developed a global reputation, fetching higher prices than Burgundy or Bordeaux. Unfortunately, the destruction of vineyards during WWII and the subsequent focus on quantity over quality quickly degraded the region’s reputation.

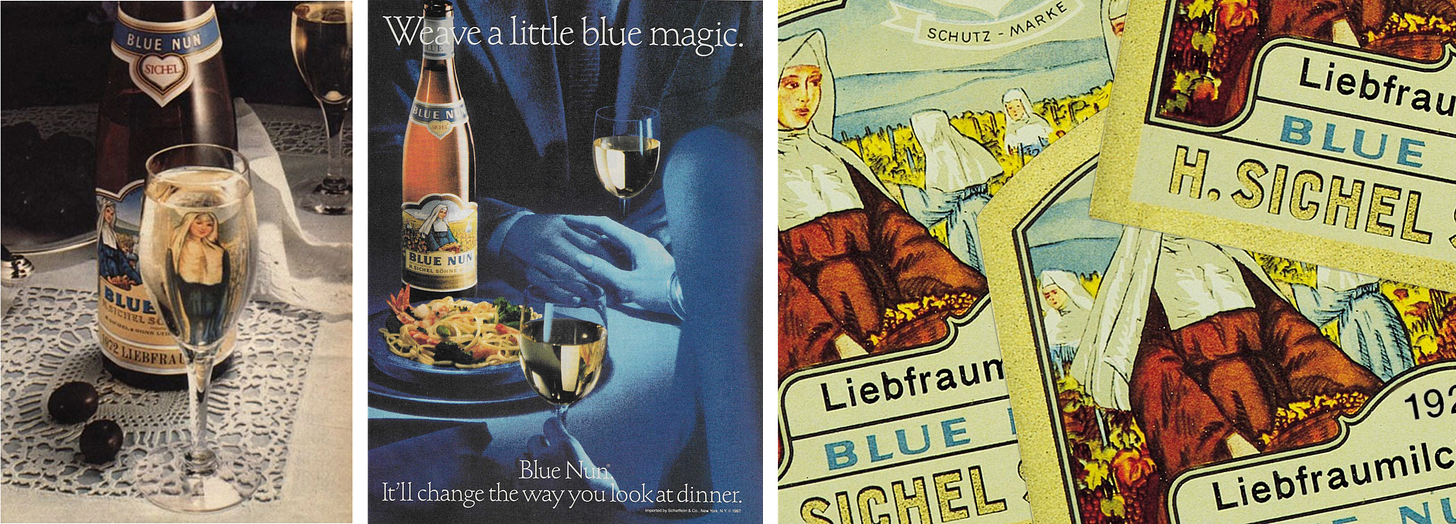

The breakout success of Blue Nun, which is often considered the first truly global mass-market wine brand (an unexpected distinction for a German wine), reinforced to consumers that German wine is sweet, cheap, and lower quality. To this day, riesling has a bit of a mixed reputation for many, still associated with sweet, dessert wines.

Luckily things began to turn around with the introduction of German wine laws in the 1970s. We covered the details of that last week icymi:

These regulations were instrumental in refining viticultural practices, focusing sharply on quality, designation, and the geographical nuances that make each wine unique. This legislative overhaul played a crucial role in re-establishing Mosel wines on the world stage, restoring their reputation as some of the finest wines characterized by their nuanced flavors and remarkable aging potential.

How to choose a bottle

Riesling is one of those wines that is fawned over by sommeliers but overlooked by the average wine drinker. To me, this stems from riesling’s versatility. Or, said another way, the unpredictability of these wines. To a somm, this is thrilling. Each wine it’s own beautiful creation ready to be analyzed, unpacked and discussed. But for someone just trying to grab a bottle to have with dinner, it’s a nightmare. Is it sweet? Is it dry?

Complex and bureaucratic labeling is not typically seen as an effective consumer marketing strategy. Especially when everyone’s greatest fear is accidentally ordering a sweet wine. While there are plenty of easy, sweet, fruity (mass-produced) options, if you are looking to discover some gems from this diverse region, here are my recommendations — many of these are lesser-known producers who offer remarkable value for the price.

Vollenweider - Known primarily for riesling, this winery has gained a reputation for producing intense, mineral-driven wines that punch well above their weight in terms of price.

Peter Lauer - Positioned in the Saar tributary of the Mosel, Lauer produces a range of riesling styles from dry to sweet. The wines are noted for their precision and affordability, especially their Barrel X entry-level wine.

Julian Haart - A relatively young winery, Julian Haart offers wines that are a great introduction to the Mosel's potential, with a focus on balance and purity of fruit.

A.J. Adam - Another relatively new name that has quickly become a connoisseur’s favorite for both dry and sweet rieslings. The wines offer exceptional value, showcasing meticulous vineyard management and winemaking.

Hofgut Falkenstein - This winery produces traditionally styled, dry and semi-dry rieslings that are very affordable. They are renowned for their rigorous adherence to traditional winemaking methods, which include using old oak barrels and wild yeasts.

Clemens Busch - A pioneer of biodynamic viticulture in the Mosel, Clemens Busch produces rieslings that are complex and have a distinct sense of place. The wines are remarkably affordable given their quality and the dedication behind them.

What I tried this month:

2022 Brand Riesling Trocken (this one is actually from Pfalz but it’s one of the best under $20 bottles that is in my regular rotation).